It was time for the monthly meeting of the Committee for the Advancement of Men in Equine Literature. From the very dawn of the pony book, it had worked tirelessly to ensure the proper representation of men and boys in equine literature for the young. Today was no different.

There was always a pre-meeting lunch, and it had been a particularly good one. Most of the committee members were still thinking fondly of the crème caramel they had just put away as they settled around the table.

“It really won’t do, you know.”

Those of the committee who had moved on from thinking of crème caramel and to that day’s agenda looked round at Captain Cholly-Sawcutt, the former international show-jumper.

Major Holbrooke shifted uncomfortably. The old committee room chairs had been very conducive to a short nap when the wordier committee members had got into their stride. There was no danger at all of falling asleep on the new chairs one of the more radical young committee members had insisted on importing. He sighed. Life had never been particularly peaceful when he was involved with the Barsetshire Pony Club, but at least it had not involved committees in Chatton. Or uncomfortable chairs. Or Captain Cholly-Sawcutt. He sighed, grateful that at least thus far, no author had yet succeeded in shoehorning the two of them into the same story.

“It really won’t do,” Captain Cholly-Sawcutt said again, and he rapped the table sharply.

One of the other committee members, whose head had been dropping onto his chest after the excellent lunch the club had provided, sat up with a start. He winced as his shoulder blades hit the edge of the new chair.

“What won’t do?” Major Holbrooke asked, although having seen the books submitted that month, he had an uncomfortable feeling he already knew the answer.

Captain Cholly-Sawcutt drew himself up and surveyed the table. The more nervous committee members shifted uneasily, aware the captain was in the grip of some strong emotion.

“These!” he cried, with a break in his voice, gesturing towards a pile of gaily jacketed books on the committee table. “Just look at them!”

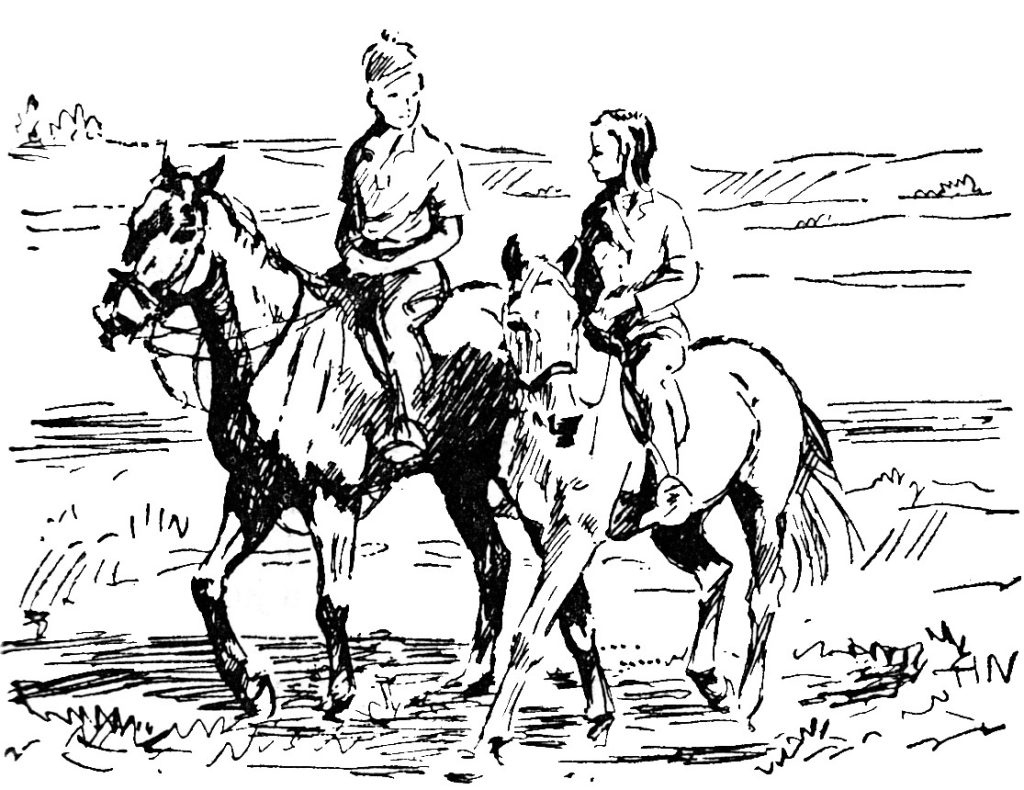

“Jolly nice set of books, if you ask me, old man,” said the oldest member. “Fellow who did the illustrating seems to know one end of a horse from the other.”

Captain Cholly-Sawcutt made a visible effort to collect himself. “It is,” he said, “merely gilding the lily. No one,” he went on, picking up Jennie and the Dressage Pony, “would guess, looking at this, I admit, excellent illustration, and anticipate what horrors lie within. Do you realise that only one judge is a man? And no one appears to have even served in the Army, let alone been an officer. And those men and boys that do appear—hopeless. The indignities they are forced to endure are wretched. We must not forget,” he went on, fixing each member of the committee in turn with a pleading glance, “that we will never achieve our mission if we let this sort of thing go unchecked.”

Major Holbrooke sighed. “I thought we had agreed at our last meeting that some sort of balance between the sexes was beneficial.”

“Speak for yourself,” someone muttered. Major Holbrooke looked down the table. He closed his eyes for a second and took a deep breath. This particular committee member had been on the committee for some months, but this was the first meeting he had bothered to attend. The Major had hoped that perhaps he would have improved over the years, but the only difference between the Christopher Minton he had taught during his Pony Club days and the one he saw before him was that this one wore better suits.

“If you ask me,” Christopher said, “what we need to agree is the abolition of men in pony books. Don’t give these authors the opportunity to make us look like fools.”

“I say, old chap,” one of the older members said. “Some of us do come over quite well. I think there’s a place for all.”

Christopher scowled down the table at Colonel Llewellyn. The major had been unable to prevent Christopher and the Colonel sitting next to each other at lunch, and Christopher had made his contempt for the Colonel and his home of rest for horses and his eccentric staff only too clear.

“Things have moved on since your time, Colonel,” he said. “You simply don’t understand what it’s like for me. I’m an Oxford blue, for goodness’ sake. Won the boat race. Have a promising career at the bar. Does any woman I meet want to talk about any of it? No. The moment they find out I’m the Barsetshire Christopher Minton, that’s it. How’s Fireworks, they ask. Is he having a lovely retirement, they want to know. Wretched pony was never good for anything, but that’s all anyone wants to talk about. I tell you, gentlemen, it has ruined my life.”

The Major was hard put not to roll his eyes.

“Exactly,” Captain Cholly-Sawcutt said, gripping the table so hard his knuckles went white. “Exactly. None of these women think what it’s like to be us. They simply slap us in these books, and then leave us to it while they rake in the royalties.”

“Fred, old chap,” one of the younger committee members went on. “I think the readers like you. And that Martin fellow. There’s really no need to worry.”

Captain Cholly-Sawcutt released his death grip on the table, but only a little. “Like me? I’m an international show jumper, but does anyone know me as that? No. I’m a figure of fun. It’s all right for you. You’re a figure of romance. Everyone is agog to know whether you kissed that girl or not.”

Major Holbrooke looked hard at Henry, who at least had the grace to look embarrassed.

“You needn’t worry about Miss Kettering,” the Major said. “She has better things to think about than my nephew. She’s halfway through her PhD, and her first book will be coming out soon.”

The committee, almost as one man, turned round and looked at Major Holbrooke.

The oldest member came to with a start. “She’s written a book, you say? Without consulting us? An unauthorised book?”

“This,” stuttered Captain Cholly-Sawcutt, “this is what happens when you let girls do what they want. When they don’t do secretarial courses. When you let them go to university, and … and … “

“Think their own thoughts?” Major Holbrooke enquired, gently.

“That’s as maybe,” Henry broke in. “What I want to know is whether I’m in this book of Noel’s. I mean, that Pony Club Camp book was bad enough. And at least you’re not married, Christopher,” he went on. “Poor Christo has developed the most frightful complex. Everyone thinks she must be Noel. She’s taken to wearing a badge.”

“I don’t think the committee, or you, need concern itself with A New Analysis of the Poems of Sappho,” Major Holbrooke broke in.

Colonel Llewellyn looked round the table, his face a study in bewilderment.

“Noel’s book,” the Major went on, turning to his nephew. “She appears to have avoided the Pony Club altogether. Not everything need centre on you, Henry.”

Henry pulled a face. “It would never be allowed in the army,” he muttered.

“We’ve simply got to hammer into these women’s heads the need to stuff their books with female characters,” Christopher said. “It’s simply not good enough. Why can’t they leave us out of it? They can’t even get their facts right.”

Captain Cholly-Sawcutt sniffed. “Exactly. If that Ferguson woman had only consulted me, I’d have told her never to let a dandy brush near that pony’s tail.”

“Or let her readers think a serpentine was an immensely complicated dressage movement,” Henry interrupted, with a smirk.

The youngest element of the committee, who tended to crowd together nearest the door, sniggered. Major Holbrooke looked at them steadily. He had never quite succeeded in deciding which of these boys was which. Two of them, he knew, had been responsible for a trekking centre, and at least one of them had had a furious argument with someone called Jackie over a pony someone had let loose. Or was it a problem with getting stuck on an island? Or some other, water-bound disaster? Major Holbrooke was never quite sure how they had got on to the committee in the first place, but here they were.

“They should just leave us boys to it,” one of them said.

“It’s about time they stood aside and let the boys have their rightful place,” another replied. “We’ll have our own books. We don’t need them. The moment us boys take over the books no one will bother with the girls.”

“Quite right,” Colonel Cholly-Sawcutt said. “I knew I was doing the right thing when Miss Berrisford suggested you for the committee. And besides, Holbrooke, just look how these women make us appear! We’ve simply got to stop it. We are there as nothing more than idiots. Idiots and … and … philanderers.”

“It was just one kiss,” Henry said. “That was all. Hardly counts as philandering in my book.”

“At least you weren’t portrayed as a fool who couldn’t teach his own daughters to ride.”

“You couldn’t, old chap,” said Colonel Llewellyn. “You couldn’t. And at least Mrs Ferguson did agree to only feature half the family. Never let on there were six of them, and the three she didn’t mention even worse than the ones she did.”

Major Holbrooke could see that matters were about to become heated.

“That’s ancient history,” he said, hurriedly, “and nothing to do with what we need to discuss: the vacancy on the committee.”

“Ah,” said Henry. “I know just the chap …”

“I thought you might,” Major Holbrooke said, “know a chap. What our constitution does allow is for the chairman to co-opt a new member, and so that’s what I’ve done.” He had been rather disappointed that Miss Manders had not been there for the beginning of the meeting, having failed to find somewhere suitable to stable the chestnut Arab mare she had insisted on bringing with her. Nevertheless, she would prove invigorating. And she would certainly make a difference. The Major foresaw all sorts of opportunities for men in equine literature: as potters, farmers, and perhaps even vegans. He looked round the committee.

There was a complete and utter silence.

“You’ve done what?” said the oldest member. “Do any of us know this man you’ve so arrogantly co-opted? How do we know he’ll fit in? Fight with the rest of us to improve the perception of men in the pony book?”

“Or remove us altogether,” called one of the younger members. “Will no one think of the men?”

There was a murmur of agreement from round the table.

“As a matter of fact, Major, you needn’t worry about co-opting anybody,” Christopher went on, “I’ve been doing a bit of research myself. I hereby invoke section 10, subsection B point three of our constitution.”

“Subsection B point three?” gasped the Colonel.

Christopher looked round the committee in satisfaction. Henry gave a guilty, sideways glance at his uncle. Captain Cholly-Sawcutt looked determinedly at the table.

“Yes,” Christopher said. “I hereby declare that by a majority vote of the committee, I am now chairman of CAMEL. Our new mission, as my young friends in the corner have suggested, is to produce our own books. Men and boys will return to their rightful place at the centre of pony stories; a centre denied to us for decades. We shall stem this rampant tide of equestrian femininity.”

Major Holbrooke looked round at the committee members. He realised he was not particularly surprised by what was happening; only surprised it had taken this long. This, he presumed, was what Christopher had been up to in the months before his first meeting. The Major considered for a moment. The writing, he could see, was on the wall. He bowed his head to the committee. “It has been a pleasure, gentlemen. I suggest we reconvene in ten years’ time and see how your campaign has gone.”

For a second, the Major saw a flicker of doubt cross Christopher’s face, but it was soon replaced by his customary smugness. “Ten years it is then, Georgie old chap,” he said. “The champagne’ll be on me.”

“Hear, hear,” said the members. “Hear, hear.”

With thanks to Josephine Pullein-Thompson, Ruby Ferguson, Monica Dickens, Patricia Leitch and Judith M Berrisford, whose works I have ruthlessly plundered.

Leave a Reply to Catherine Holland-Bax Cancel reply